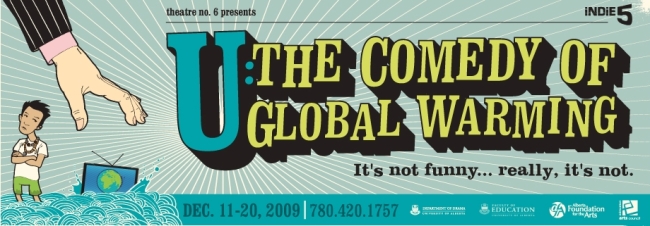

I’ve just finished co-writing an article on the use of satire in climate change communication and wanted to share some of our findings here. Back in 2010 my former Cardiff University colleague Grace Reid (now at University of Alberta, Canada) invited me to work with her on a science communication project that was focusing on the satirical stage play U: The Comedy of Global Warming. Despite being busy with developing the play, writer / director Ian Leung was happy to take an active part in our project. As such, this is what is often termed a knowledge transfer or knowledge exchange project. Ian helped us learn about some of the political, creative and practical issues involved in such a production, and we got to share our research findings with someone who could use them in their work.

So, here’s what we did: The play ran for nine days in Edmonton, Alberta, and we conducted one interview with Ian beforehand and a second one after it had finished. We also did a performance analysis of the play itself, based on Grace’s observations from attending multiple performances, and on two DVD recordings provided by Ian. Finally, we did questionnaires with 87 of the 180 or so people who saw the play, and two follow-up focus groups with six audience members in each.

U: The Comedy of Global Warming has a local setting and deals with some of the issues around living in an oil-rich province while being aware of debates around climate change effects. It focuses on the gay love triangle between oil executive Albert A. Oyl (Al), Tuvaluan climate change refugee Tivo, and TV presenter Clinton Carew. The premise is that the island nation of Tuvalu is disappearing into the ocean because of climate change, and Al has “sponsored” Tivo so that he can come to Canada. This turns out to mean that Tivo lives in Al’s house as a servant, and we also see Al making forceful sexual advances towards him. Tivo then ends up dating Clinton, who presents a TV show on climate change. This show-within-a show device involves big screens displaying video interviews with real-life scientists and politicians discussing climate change issues. The love triangle narrative is interspersed with these interview segments, as well as speeches addressing the audience, musical performances and audience participation. The play also has a companion website (www.albertaville.ca), which includes information about its interview subjects, as well as recommendations for various resources on climate change issues and suggestions for how citizens can get involved.

Our project was concerned with several key issues, but here I want to focus specifically on what we found in terms of how satire might be used in climate change communication. We hope this can be generalised beyond our particular case study, and that it might be helpful for communicators interested in using satire (or other humorous modes) to engage audiences in climate change debates, whether through theatre, screen media or other cultural forms.

The current ideal in science communication is to encourage citizens to engage actively with science. This has replaced the one-way model of scientists trying to transmit factual information to lay people. With that in mind, we want to highlight two important benefits of using satire to promote active public engagement, and two significant challenges.

First of all, because humour tends to involve comic incongruities of some sort, these conflicting discourses create a certain textual ambiguity. That doesn’t mean the joker’s intentions can’t be completely obvious to anyone from a similar cultural context, but humorous texts can leave quite a bit of room for interpretation. It depends, in part, on how much creators want to anchor the meaning, and how skilful they are at doing so. I’m sure we can all think of numerous occasions where jokes have fallen flat or been misunderstood, though, so this is tricky territory. For climate change communication, such textual openness can be used to encourage audiences to make sense of representations based on their local context and their own experiences. It can also invite audiences to question what they’re seeing, to reflect on ideas and look for more information. That would help prolong audience engagement with climate change issues beyond the moment of reception.

The second benefit we want to highlight is that using humour can help avoid what is known, in the parlance of our times, as freaking people out. Climate change effects are pretty scary, and telling people about them can make them feel so overwhelmed that they end up concluding that we’re all doomed and there’s no point trying to do anything about it. But humour can help us explore difficult issues in a “safe” space, and that might make it easier to get audiences interested in what is happening without frightening them too much.

However, that leads me onto the first of the two challenges we want to focus on. The comic distance that can cushion us from these scary things can also prevent us from taking them seriously enough. For climate change communicators, this could clearly undermine the primary purpose of their text. The ideas that they are presenting cannot remain confined to the realm of humour – they must be more than jokes, and they have to include productive proposals to climate change debates. In the case of U: The Comedy of Global Warming, Ian’s use of video interviews with scientists and politicians kept disrupting the humorous tone, while the website also offered audiences practical means of finding information and taking action.

Having said that, if you’re going to sell something as satire, audiences will expect laughs. And while predicting what people will find funny is always going to be difficult, getting people to laugh at satire tends to require that they both enjoy the particular humour style(s) adopted in the text and that they (at least to a certain extent) sympathise with the underlying critique. This means that satirists will need to consider their target audience’s attitudes towards climate change as well as their humour preferences, and those may depend on factors such as age, class, education, gender, previous cultural consumption, and so on. This means that satire may be less useful for targeting diverse publics and more suitable for communication specifically tailored to niche groups.

Funding:

This research was funded by the CRYSTAL-Alberta Science Education Centre.